Since the 2000s, many software companies have been moving to agile software development practices. Agile development[1] (Kanban, lean, etc) is a set of methodologies designed to facilitate fast, high-impact software. Agile development has driven success in consumer-facing industries like e-commerce and social media or highly modular software like manufacturing. Medical software leaders have noticed this success and are either already using or transitioning to agile software development.

So why haven’t we seen a revolution in scalable healthcare software? Why does healthcare continue to represent a larger and larger fraction of the US GDP? Why is it estimated that healthcare software is driving a large portion of healthcare organization burnout?

In our opinion, agile doesn’t work for healthcare software development. We’ll say that again. Healthcare has unique challenges that interfere with the basic principles of agile.

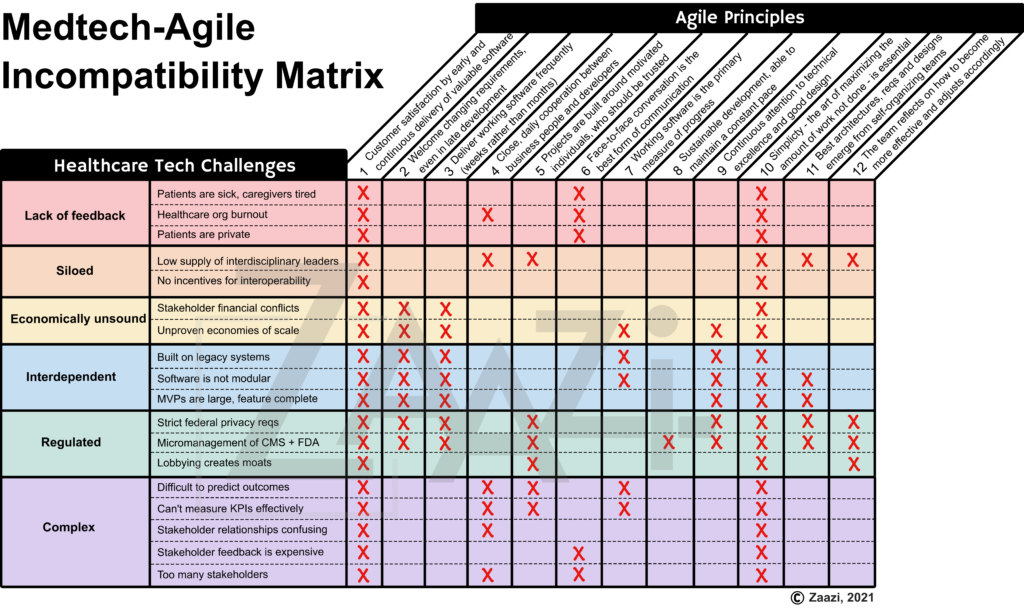

Barriers to healthcare agile development include lack of stakeholder feedback, siloed development in an interdependent industry, high regulation, non-intuitive complexity and financial restraints.

Here’s a chart of how these healthcare challenges interact with the 12 agile principles.

Barriers to Agile Development in Healthcare

Let’s take a look at the first principle.

-

- Customer satisfaction by early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

If we were developing a manifesto, we would put the most important principle at the top. Unfortunately, almost everything about healthcare development interferes with the first principle of agile.

Understanding the current state of healthcare is difficult

To build “valuable” software, you must identify a solvable pain point in the industry. This begins with a deep understanding of how things are currently done in the US healthcare system.

To build “valuable” software, you must identify a solvable pain point in the industry. This begins with a deep understanding of how things are currently done in the US healthcare system.

US healthcare is overwhelmingly, disgustingly complicated. There is an ever-increasing number of stakeholders including patients, care providers, insurers, hospitals, medical equipment firms, the federal and state governments, technologists, pharmaceutical companies, labs, data repositories, nursing home facilities, rehab centers and social services. Understanding this morass of healthcare complexity seems like a losing battle. Government regulation, quality metrics, legal liability, security requirements and insurance policies cause mass upheaval on at least an annual basis. Because insurance is often tied to an employer, patients are often transitioning between plans.

To add insult to injury, these stakeholders often have opposing incentives[2]. Insurance companies (payers) often offer reimbursement that values volume over quality. Some physicians believe this has led to improper standardization of treatments, at the expense of patient health. Care providers often want to give the best care available, but this is limited by financial reality. What level of treatment does US society believe is expected and reasonable?

The stakeholders are intricately connected in a delicate balance of interdependence. Introducing software into this complex system can have unintended consequences[3]. There is now a name for harm caused (at least in part) by the application of healthcare information technology: e-iatrogenesis[4]. One striking example highlighted by this paper[4] involves an increase in pediatric mortality after the implementation of an EHR that required care providers to “admit” a patient before orders could be entered. This meant that newly-arrived critical patients had delays in their treatments, sometimes resulting in harm.

The US healthcare system is different from any other healthcare system in the world. When a patient has health insurance it is purchased in a marketplace or provided by the government. There are several models of reimbursement in the insurance industry including fee-for-service, pay-for-performance, HMOs and DRGs. There is little consensus[5] about which reimbursement model is effective in the US. About 10% of the US population is uninsured (as of 2019).[6] Because of this, there are many other third party models trying to improve affordable access to healthcare. These include direct primary care, concierge physicians and direct-to-patient pharmacies. Experience in other nations’ health systems is not sufficient to understand the US market.

The US healthcare system is not a free market, making the economic picture difficult to comprehend and predict. The US spends more on healthcare as a percentage of our GDP than any other developed country.[7] We have some of the highest rates of suicide, chronic disease burden and obesity amongst other developed countries.[7] This has resulted in some of the lowest healthcare access rates of any developed nation.[7] Our current model of healthcare delivery is not economically viable.[8] And so far, no country in the world has figured out how to scale quality healthcare to hundreds of millions of people. This means that healthcare software developed on this financial model not only has a shelf life but could contribute to rising healthcare costs.

Understanding the current US healthcare market is so difficult, we’ve observed companies that don’t perform any market research at all.

It’s easy to solve the wrong problem in healthcare

But let’s say you understand the current US system and the interplay between stakeholders. To truly understand a market pain point (and thus what solutions would address this pain point), you must understand the fundamental experience of a patient and a care provider. The interplay between the patient and care provider is the entire essence of healthcare. But oddly, we’ve observed the most frequent medtech leadership team is composed of a business executive and a technical lead, with an optional provider advisor.

Fortunately (but also, unfortunately), the majority of working adults in the United States are healthy. Some have had isolated health incidents, but few have significant experience as a patient in the US healthcare system. Those that have had significant experience as a patient are often reluctant to disclose that experience.[9] In the US, the chronically ill are often viewed as “less than”. People with disabilities are employed at significantly lower rates than nondisabled people.[10] More often, companies view patients as an intermittent “survey source” rather than as a collaborator.

Care providers are almost entirely isolated from industry software development. While software companies sometimes solicit provider feedback, they do not invite (or can’t afford) providers as collaborators. For the rare software companies that employ care provider leaders, these are often figurehead positions with limited (or no) impact on company strategy. Sometimes, the care provider’s perspective is seen as sufficiently holistic to cover the patient’s perspective!

It is rare to find an interdisciplinary leader in the US healthcare system with a fundamental understanding of the patient and provider experience. Healthcare education is expensive, with physician student debt averaging $241,600.[11], with loans that are increasingly impossible to pay back with current salaries.[12] Schools usher students into clinical medicine with almost rabid intensity. Clinical students are not educated on alternative or supplemental careers in industry. But even if we removed these barriers, clinical care doesn’t lend itself to being a “part-time job”. Being a clinical care provider in the US requires extensive administrative burden including continuing education, yearly licensing requirements, liability insurance and mandatory long hours. The long-hour requirements alone preclude many folks with a chronic illness from obtaining a clinical degree, despite evidence suggesting healthcare providers who identify as disabled improve health outcomes for their patients.[13] Many clinical care programs continue to use antiquated testing mechanisms[14] and physical entry requirements. For example, you will not be accepted to medical school if you cannot perform CPR[15], even if you are specializing in radiology. This further restricts patients from becoming providers. Even when an interdisciplinary leader is found with patient and provider experience, companies often view this as a luxury rather than a necessity.

It is difficult to find and retain the right collaborators

So why don’t companies simply hire a patient, provider and a caregiver to help with strategy? Because patients are sick, caregivers are exhausted and providers are busy.

For a patient and caregiver to be engaged in a product, they must be properly compensated for their perspective. Patients and caregivers are often fighting for the patient’s life, and are almost certainly under financial strain. A company must demonstrate they respect that time and effort is a precious asset for patients and care providers. But most often, patients and caregivers are seen as laypeople, if they are even considered at all. In the rare instances when they are recruited, it is for minimum wage (or close to it).

Care providers must be compensated for the switching costs between their clinical practice and industry work. As mentioned above, providers are often overworked. This means that time spent in industry will likely be debited from family or relaxation time. This sacrifice must be reflected in their compensation.

Even when a business can afford this compensation (which is rare), financial incentive is not sufficient. All 3 of these stakeholders have been betrayed by healthcare IT. Healthcare organizations and the US government have inflicted burnout on care providers at mass scale, while insisting that electronic transformation is improving patient care. The reality is that HIT has caused just as many problems as it has solved[16]. Providers have watched their patient visits morph from human connection to glorified note-taking[17]. Some studies estimate that physicians spend more time documenting than seeing their patients[18]. Patients have noticed despite their increase in complicated health issues[18], their overall provider facetime (without the physician typing into an EHR) has stayed the same or decreased.[19] Caregivers have watched their loved ones sicken as the US healthcare system is overburdened or is too expensive to afford. To enlist help from patients, caregivers and providers, a firm must convince these stakeholders that their software will be different from what has come before. The leadership team must have the humility to listen to those who understand the fundamental pain points in healthcare, and act in ways that align with this feedback.

Healthcare MVPs are enormous with limited innovation

But let’s say your business obtains and embeds a patient and a health care provider (or interdisciplinary leader) into their software development team. Now it’s time to build an MVP and show traction. But healthcare software does not lend itself to lean MVPs.

First, healthcare is a highly regulated industry. Federal law requires utmost security around protected healthcare information (PHI). While this has noble intentions, the result is that healthcare and software organizations have some of the highest breach costs of any industry.[20] Consequences for violating this law include public embarrassment, fines and possibly jail.

Federal laws have also been passed around Medicare and Medicaid in order to curb healthcare costs. In order for healthcare organizations to obtain full reimbursement for their CMS claims, they must use a “certified EHR technology”. This certification requires passing 20+ tests on interoperability, data security and architecture. It can take anywhere from 6 months to several years to complete.

Even when federal law doesn’t specify restrictions around software, the law can have dire implications for software. For example, physicians are required to complete very specific tasks to obtain reimbursement from CMS, even if those tasks don’t improve that patient’s outcomes. For example, a provider may have to document the fall risk of a patient that is unconscious on a ventilator before billing. This is reflected in the absurd data collection requirements of modern EHRs.

State laws complicate matters (especially in the age of a dawning global economy) by regulating additional PHI security requirements, care provider licensing and mandatory prescription screening. This is most evident in pre-pandemic telemedicine where a provider licensed in Massachusetts could not see a patient 5 miles away, across the border in Rhode Island[21] (without paying thousands of dollars for licensure in RI).

High regulation is compounded by the previously mentioned complexity to create enormous software products. This has created an environment where a company must develop 20+ large features as table stakes to even consider entering the healthcare market. But it’s not enough for a healthcare software product to be “as good as” something on the market. There must be a differentiator that overcomes the software switching costs. Federal law requires the storage of medical records for 7 years. So many organizations are faced with still paying SaaS monthly fees for their old software if they move to a competitor’s software.

It is risky to implement new software in a health system. A healthcare system is precariously balanced on a morass of legacy systems at varying levels of modernization. These include antiquated imaging software, old FTP connections and unstable APIs. New software must seamlessly integrate with all of these because a health system cannot afford to replace the entire software landscape simultaneously.

Unfortunately, many of these legacy systems have limited interoperability options. This can be because of technical or political barriers. In an era where the public’s data can be monopolized into lucrative revenue streams, many healthcare software companies do not want to share data collected by their software. Forcing interoperability was one of the key drivers behind the 21st Century Cures Act passed by the federal government.

Even when a legacy system does play nice, versioning is often a nightmare. Every EHR (and sometimes different versions of the same EHR) has differing APIs. Many legacy systems have a piecemeal architecture, so some data structures don’t make sense. Even when the EHR API remains consistent, care providers may enter data in odd places (trying to apply the only tool they have to improve human health). Care providers within the same practice can use the same healthcare software in various ways. This forces a new healthcare software company to make a large investment to integrate their software before they can obtain any ROI. These integrations are often so complicated that a company can only integrate serially, not in parallel. This limits the adoption rate of new healthcare software.

The interdependence on legacy systems also stifles creativity. Legacy systems can invalidate a new software’s security or innovation strategy, causing further antiquated systems to be developed to make revenue numbers.

The push towards interoperability has caused the development of ways to structure and communicate clinical data between systems. Unfortunately, the new standard (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, abbreviated FHIR, pronounced “fire”) has differing versions and much ambiguity about how clinical data can be communicated. Although this is better than what we had, it has not allowed industry-changing software development.

All of this is a moot point if the 800 lbs gorillas don’t want your new software in their ecosystem. Because almost all clinical data flows through an EHR, they hold an unusual amount of sway in healthcare software. For example, EPIC EMR has a complicated history of blocking medical record transfers which has resulted in EPIC controlling 39% of the hospital EMR market in the US.[22][24] In fact, we (and other consultancies) have seen healthcare organizations that will not buy useful software unless it is on EPIC’s integration roadmap.[23] Additionally, large EMR vendors typically force large healthcare organizations to “lock-in” to their solution for 10 years or more.[24]

New software can also be invalidated by a new federal or state law. Lobbyists are employed by many large healthcare software companies, professional care provider organizations (like the AMA) and insurance companies. If a new software product threatens their revenue or existence, they may try to pass regulation that restricts this product’s impact.

Stakeholder feedback is expensive or impossible

But let’s say that you find a software niche that is modular, secure and interoperable. You’ve snuck past the 800 lb gorillas, and you’ve built your MVP. Now how to measure traction?

Because healthcare organizations can’t use a feature-incomplete product, an MVP probably hasn’t received much feedback yet. In fact, it may be difficult to even figure out which stakeholder the feedback should come from. If you are building an EHR, is it more important to have physician adoption or positive patient health outcomes? What if you can deliver one, but not the other? What if the physicians like your product, but health system administrators think it is too expensive? How do you decide which stakeholders are vital to the system, and which are not?

Even when the customer is obvious, it is not easy to obtain feedback. Many software glitches won’t be visible until the system is fully operational and integrated into the legacy tech stack. As previously mentioned, providers are busy. They have little time or incentive to give product feedback. Especially when their feedback has been consistently ignored for over 10 years.

How do you measure secondary stakeholder effects? For example, when EHRs were first mandated, it was expected that patient care would greatly benefit. And in some ways, patient care did improve. At least provider handwriting was standardized into type font! But in many ways, EHRs have caused a catastrophic collapse of the patient-provider relationship. It is difficult to imagine that EHR companies studied this possibility before launching their software.

But even if the EHR had attempted to study this outcome, they likely would not have uncovered it. Because of healthcare’s complex ecosystem, disturbances in the balance are often not felt or understood until years later. Many secondary stakeholders may not even understand what is causing their pain. For example, patients almost never interact with an EHR directly. From their perspective, physicians are simply too busy.

Even when patients do understand that a software product has caused them harm, they may be reluctant to give feedback. If Facebook launches a new feature, there will be 1000 Tweets about it within an hour. Patients getting chemotherapy likely don’t want to post their evaluation of an oncologic telehealth software on their social media.

But even if we had data from all the various stakeholders, it would be difficult to prove positive health outcomes. We can’t yet measure human health very well. We have data measuring minute changes in human physiology, but they don’t correlate with clinical events. We have limited insight into the severity of disease. For example, we can judge how severe a patient’s diabetes might be through data. But we can’t look at the data of a patient and say “healthy” or “not healthy”. It’s a complicated continuum.

So if we can’t use agile, what’s the solution?

Let’s look at our first agile principle again:

Customer satisfaction by early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

Hopefully, by now, you understand how challenging it is for a software company to develop lean, modular healthcare software that has continuous stakeholder feedback with metrics that represent value.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a silver bullet. We don’t have an agile alternative to pitch. But there are some recommendations that emerge from this analysis that can help healthcare software companies build a product more aligned towards valuable outcomes.

- Stop applying agile to parts of a business that don’t lend themselves to agile. Agile is not a magic strategy. There are aspects of agile that can and should be applied to healthcare software. Harvard Business Review and Bain have helpful articles[25][26] for you to identify which parts of your organization might benefit from agile, and which don’t.

- Do market research even though it’s hard. High-cost market research is still cheaper than 10 engineers building the wrong product for 6 months.

- Invest in strategic thinking. Find patients, caregivers, providers and interdisciplinary healthcare leaders that can challenge your product. The more criticism you gather (and address), the more likely your company is to hone in on how to solve a real pain point. Appreciate the wisdom of their analysis with the same intensity that you would listen to advice from Steve Jobs.

- Show traction amongst the top 5 stakeholders related to your product, not just the target customer. Your product may be revolutionary, but you still can only eat a hamburger one bite at a time.

- Consider taking a bigger swing. The US healthcare system is badly broken. Iterating on a rotten foundation is not likely to result in a fortified, valuable product. Are there niches where your company could reimagine a portion of the healthcare workflow?

- Lastly, remind your company and yourself of the bigger picture. The worst outcome of badly designed healthcare software is not obsolescence. It’s harm.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agile_software_development. Accessed 6/10/21.

- Avi Mamidi, PharmD1 ; Elizabeth Oyekan, PharmD, FCSHP, CPHQ2; Jeremy Schafer, PharmD, MBA3; Larry Blandford, PharmD4—Column Editor. Where Incentives Align (or Don’t) Among Health Care STakeholders and How They Are Evolving. Journal of Clinical Pathways. 2020 March. https://www.journalofclinicalpathways.com/article/where-incentives-align-or-dont-among-health-care-stakeholders-and-how-they-are-evolving. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Bloomrosen M, Starren J, Lorenzi NM, Ash JS, Patel VL, Shortliffe EH. Anticipating and addressing the unintended consequences of health IT and policy: a report from the AMIA 2009 Health Policy Meeting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(1):82-90. doi:10.1136/jamia.2010.007567. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3005876/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Bernstam EV, Hersh WR, Sim I, et al. Unintended consequences of health information technology: a need for biomedical informatics. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43(5):828-830. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2009.05.009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2891863/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Ikegami N. Fee-for-service payment – an evil practice that must be stamped out?. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(2):57-59. Published 2015 Feb 6. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4322626/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- enters for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Page last reviewed March 1, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-insurance.htm. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Tikkanen, Roosa, Abrams, Melinda K. US Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2019: Higher Spending, Worse Outcomes?. The Commonwealth Fund. 2020 Jan 30. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Why Are Americans Paying More for Healthcare?. Peter G. Peterson Foundation. 2020 Apr 20. https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2020/04/why-are-americans-paying-more-for-healthcare. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Jain-Link, Pooja, Kennedy, Julia Taylor. Why People Hide Their Disabilities at Work. Harvard Business Review. 2019 Jun 3. https://hbr.org/2019/06/why-people-hide-their-disabilities-at-work. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Economic News Release: Table A-6: Employment status of the civilian population by sex, age and disability status, not seasonally adjusted. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Last modified 2021 Jun 4. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t06.htm. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Hanson, Melanie. Average Medical School Debt. Educationdata.org. Last updated 2021 Jun 8. https://educationdata.org/average-medical-school-debt. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Barron, Daniel. Why Doctors Are Drowning in Medical School Debt. Scientific American. 2019 Jul 15. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/why-doctors-are-drowning-in-medical-school-debt/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Meeks, Lisa M. PhD; Herzer, Kurt MD, PHD, MSc; Jain, Neera R. MS. Removing Barriers and Facilitation Access: Increasing the Number of Physicians With Disabilities. J Association of American Medical Colleges. 2018;93(4):540-543. doi:10.1097/ACM0000000000002112. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2018/04000/Removing_Barriers_and_Facilitating_Access_.27.aspx. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Prober, Charles; Kolars, Joseph C,; First, Lewis R,; Melnick, Donald E. A Plea to Reassess the Role of United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 Scores in Residency Selection. J Academic Medicine. 2016;91(1):12-15. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000855. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/wk/acm/2016/00000091/00000001/art00011. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Medical Education at Yale. Yale School of Medicine. https://medicine.yale.edu/education/admissions/nonacademicconsiderations/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Tsai, Chen Hsi,; Eghdam, Aboozar,; et al. Effects of Electronic Health Implementation and Barriers to Adoption and Use: A Scoping Review and Qualitative Analysis of the Content. Life. 2020;10(327). htps://doi.org/10.3390/life10120327. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-1729/10/12/327/pdf. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Joukes E, Abu-Hanna A, Cornet R, de Keizer NF. Time Spent on Dedicated Patient Care and Documentation Tasks Before and After the Introduction of a Structured and Standardized Electronic Health Record. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(1):46-53. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1615747. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5801881/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Young RA, Burge SK, Kumar KA, Wilson JM, Ortiz DF. A Time-Motion Study of Primary Care Physicians’ Work in the Electronic Health Record Era. Fam Med. 2018;50(2):91-99. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.184803.https://journals.stfm.org/familymedicine/2018/february/young-2017-0121/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Tai-Seale, Ming; McGuire, Thomas G.; Zhang, Weimin. Time Allocation in Primary CAre Office Visits. Health Services Research. 2007;42(5):1871-1894. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00689.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00689.x?casa_token=PnZlIEA9dqEAAAAA%3Askr3OXUWLahuIHLhMD-ILY8iCO6DzallnKL2jmVzq3T1Zf3Xm0xgjULT9lIma9NwSz-_94rNqheu44A. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Landi, Healther. Average cost of healthcare data breach rises to $7.1 million, according to IBM report. Fierce Healthcare. 2020 Jul 29. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/tech/average-cost-healthcare-data-breach-rises-to-7-1m-according-to-ibm-report. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Practicing Medicine Across State Lines – It’s (Currently) Complicated. ortholive.com. 2019 Mar 14. https://www.ortholive.com/blog/practicing-medicine-across-state-lines-its-currently-complicated/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Jennings, Katie. The Billionaire Who Controls Your Medical Records. Forbes. 2021 Apr 8. https://www.forbes.com/sites/katiejennings/2021/04/08/billionaire-judy-faulkner-epic-systems/?sh=a7b6078575a0. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Turinas, Adam. Healthlaunchpad.com. 2021 May 10. <https://healthlaunchpad.com/8-most-common-healthcare-market-entry-barriers-how-to-overcome-them/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Ross Koppel, Christoph U Lehmann, Implications of an emerging EHR monoculture for hospitals and healthcare systems, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, Volume 22, Issue 2, March 2015, Pages 465–471, https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2014-003023. https://academic.oup.com/jamia/article/22/2/465/695841?login=true. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Rigby, Darrell K.; Sutherland, Jeff; Takeuchi, Hirotaka. Embracing Agile. Harvard Business Review Magazine. 2016 May. https://hbr.org/2016/05/embracing-agile. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.

- Rigby, Darrell K.; Berez, Steve; Caimi, Greg; Noble, Andrew. Agile Innovation. Bain & Company Brief. 2016 Apr 19. https://www.bain.com/insights/agile-innovation/. Accessed 2021 Jun 21.